In the closing scene of the 1977 movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind, an alien spaceship hovers above an anxious and awestruck crowd of scientists and engineers. The ship looks like a giant soup bowl, with lights filtering through openings in its hull. As the ship slowly descends to the ground, there’s an intense feeling of wonder and expectation among onlookers—a sense that a new era is dawning upon humankind.

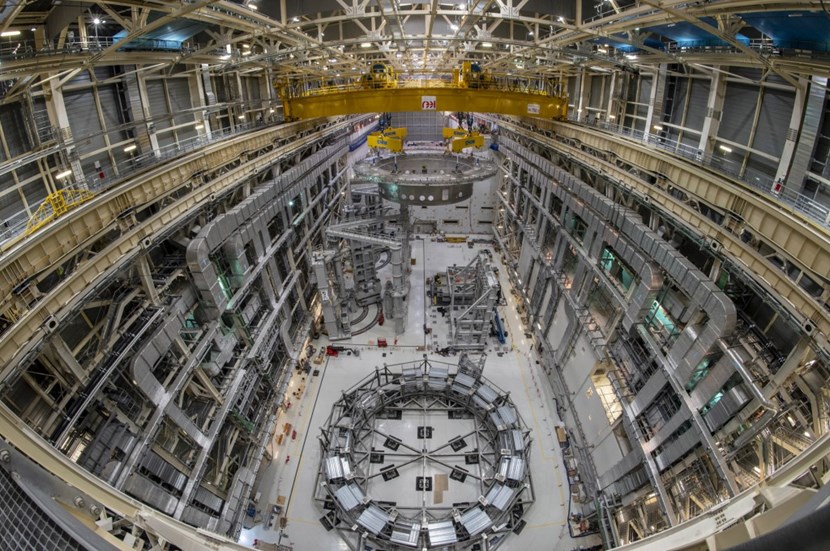

Like a scene out of Spielberg’s ”Close Encounters of the Third Kind,” the soup-plate-shaped cryostat base slowly rises from its supporting frame. A unique, one-of-a-kind operation is beginning.

On Tuesday 26 May, as the soup-bowl-shaped base of the ITER cryostat was gradually lifted from its frame, carried across the Assembly Hall to the Tokamak Building and eventually lowered into the Tokamak assembly pit, the Spielberg blockbuster was in everyone’s mind.

Not only did the component’s shape bring back images of the alien ship, it also conveyed a similar significance. With the installation of the first major machine element, humankind was taking a decisive step toward the realization of fusion energy. And by providing clean, safe and unlimited energy, fusion has the potential to alter the course of civilization.

Tuesday’s operation in the machine assembly theatre marked the culmination of a ten-year effort to design, manufacture, deliver, assemble and weld one of the most crucial components of the ITER machine—the 30-metre-high, 30-metre-in-diameter ITER cryostat (of which the base is only one part)—which will act as a thermos, insulating the magnetic system at cryogenic temperature from the outside environment.

Procured by India, manufactured in segments by Larsen & Toubro Ltd at its Hazira factory, the cryostat is assembled and welded on site under the supervision of the Indian Domestic Agency. The elements for the base section were delivered to ITER in

December 2015 and the 1,250-tonne component was finalized in July of

last year. Taking over from the Indian Domestic Agency, the ITER Organization then proceeded with “pre-assembly work” before moving the component into the Assembly Hall

one month ago.

And there it stood for a little more than one month, a giant among the other ITER giants.

Moiving one metre per minute at an altitude of 24 metres, the 1,250-tonne component travels 110 metres from the entrance of the Assembly Hall, where it had been stored since mid-April, to the opening of the Tokamak assembly pit.

Spielberg’s movie doesn’t say how long, and how carefully, the alien ship’s crew tested and rehearsed procedures before delicately landing it. For the cryostat base, these preparatory steps took the better part of one week.

The base had been assembled and welded inside a sturdy support frame, acting as a rigid exoskeleton. For the first time, the component would be lifted out of its steel cradle and it was of crucial importance to verify that the deformation incurred would remain within tolerances.

However thick the steel plates, a component as large and as heavy as the cryostat base becomes slightly flexible once suspended in the air. Despite carefully balancing the load supported by each of the crane’s four spreader beams, deflections are inevitable and acceptable as long as they remain within tolerances.

Incremental lifts, first a few centimetres, then a few metres above ground, allowed for the fine-tuning of the crane systems. These movements were interrupted at regular intervals to perform metrology surveys, ensuring that reality reflected what had been planned and modelled over the years.

And it did. By Tuesday morning, all the experts involved were confident enough to launch the actual operation—a 110-metre-long journey from one end of the building to the other, passing above and over the two 20-metre-high sector sub-assembly tools and eventually reaching the circular opening of the machine assembly pit.

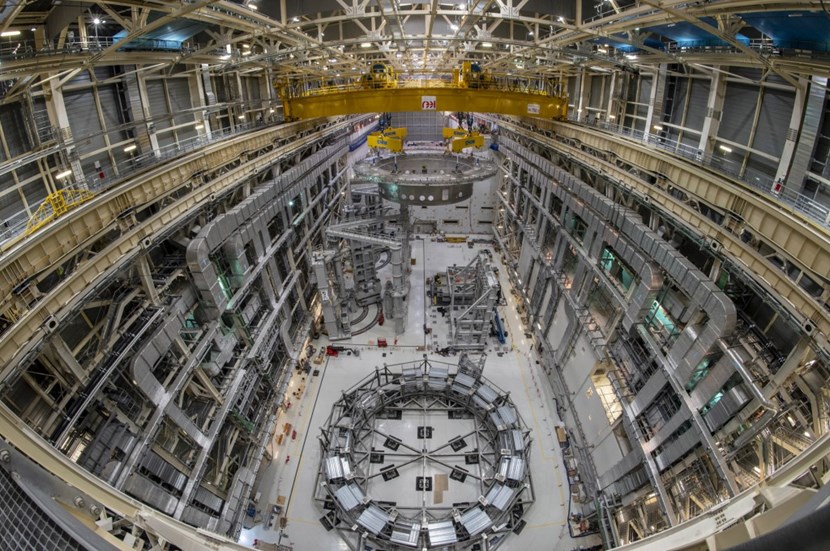

The lower part of the component is now passing the edge of the supporting crown. A pair of hydraulic jacks, located between two bearings to the left, are ready to be pumped up to act as temporary supports for the massive load.

There, one of the most delicate phases of the operation slowly unfolded as the cryostat base descended into the deep concrete cylinder, almost brushing its inner walls, to be positioned within millimetre accuracy into its support system.

At the start of the operation, ITER Director-General Bernard Bigot had stressed the unique importance of the moment and expressed his confidence in the operation’s success. “The coming moments will stand out in the minds and memories of us all,” he said. “What you will accomplish today, as a team, is something that has never been done before in history—and although you have rehearsed it many times, it will be a first-of-a-kind operation. We trust the engineering calculations, strategy and control. We trust the materials science. We trust the metrology. But my confidence today is because I trust you to work as one committed and highly professional team, convinced as we all are that failure is not an option.”

And fail it did not. By Wednesday afternoon, the first and heaviest component of the ITER machine was positioned at its final altitude a few centimetres above the hydraulic jacks that will support its weight until final metrology and adjustments are performed and the load can be transferred to the cryostat support bearings (more details in the photo gallery below).

With this spectacular achievement, a new chapter has opened in the long history of ITER.